Events

- 08.08.2022 Danube Women Stories Exhibition in Novi Sad

- 23.10.2020 Linz Kulturquartier, Reading and Discussion

- 17.-23.05.2019 Danube Women Stories in Regensburg at World Heritge Visitor Center

- 13.-20.07.2018 Danube Women Stories in Ulm Museum, International Danube Festival

Johanna Hevesi Bischitz (1827-1898), demonstrated her love for humankind as early as the Hungarian Revolution and War of Independence in 1848-49, when she cared for the wounded in her own home, located in the town of Tata. In 1866, she, along with the Chief Rabbi of Pest and 11 women, established the Israelite Women’s Association of Pest, which became an exemplary and prominently important charity institution of the capital city. Its main aim was to “offer help to chaste women living in destitution, with special regard for those who are ill of health, or unable to provide for themselves, or with child, or widowed, or orphaned”. She recognized that, as a result of growing urbanization, more and more women became vulnerable. She saw the education and training of women, as well as securing wage-earning job opportunities for them, as means to avoid falling into debauchery and prostitution. They also maintained a girls’ orphanage and shelter, where they were initially able to care for 12 orphans. This number later grew to 120. The orphanage was once visited by Empress Elisabeth of Austria, Queen of Hungary. The Women’s Association also ran a kosher soup kitchen, which offered warm meals not only to Jews, but all people in need, regardless of their religious denomination.

The headquarters of the Israelite Women’s Association of Pest was located on the corner of Kertész Street and Dob Street, in the building that today houses the Fészek Artists’ Club. The institution was financed through fundraising events and activities, such as balls, musical evenings, and theatre performances. In addition they had over 400 money boxes for collecting donations all over the city. These events also served as important gathering places for Budapest society, where anyone who was someone was expected to attend. Lujza Blaha, Ferenc Liszt and Sándor Bródy also participated in these events. And there was another important aspect to these events that should not be overlooked: they allowed a general opportunity for women to be active participants in the public sphere and paved the way for the acceptance of women’s political agency.

Johanna Bischitz is also credited with establishing the Capital’s Kindergarten Association. She was the first woman who (apart from the relatives of monarchs and from saints) was honoured by a statue posthumously in Budapest. The bust was unveiled in the building of the institution (32 Akácfa Street). József Róna’s artwork, weathered by the passing of decades, is waiting to see better days at the Hungarian Jewish Museum.

She never bore any children; she regarded her husband’s sons from his first marriage as her own. (Nobel Prize in Chemistry laureate György Hevesy was a descendent of one of the boys.)

Johanna Bischitz was accorded, on her own merit, the title of nobility along with the “Hevesi” surname by Franz Joseph I of Austria. The crowd that gathered for her final sendoff was comparable to the funeral procession of Lajos Kossuth, Hungary’s former governor-president and most popular statesman.

Various social institutions in the 6th District still bear her name today.

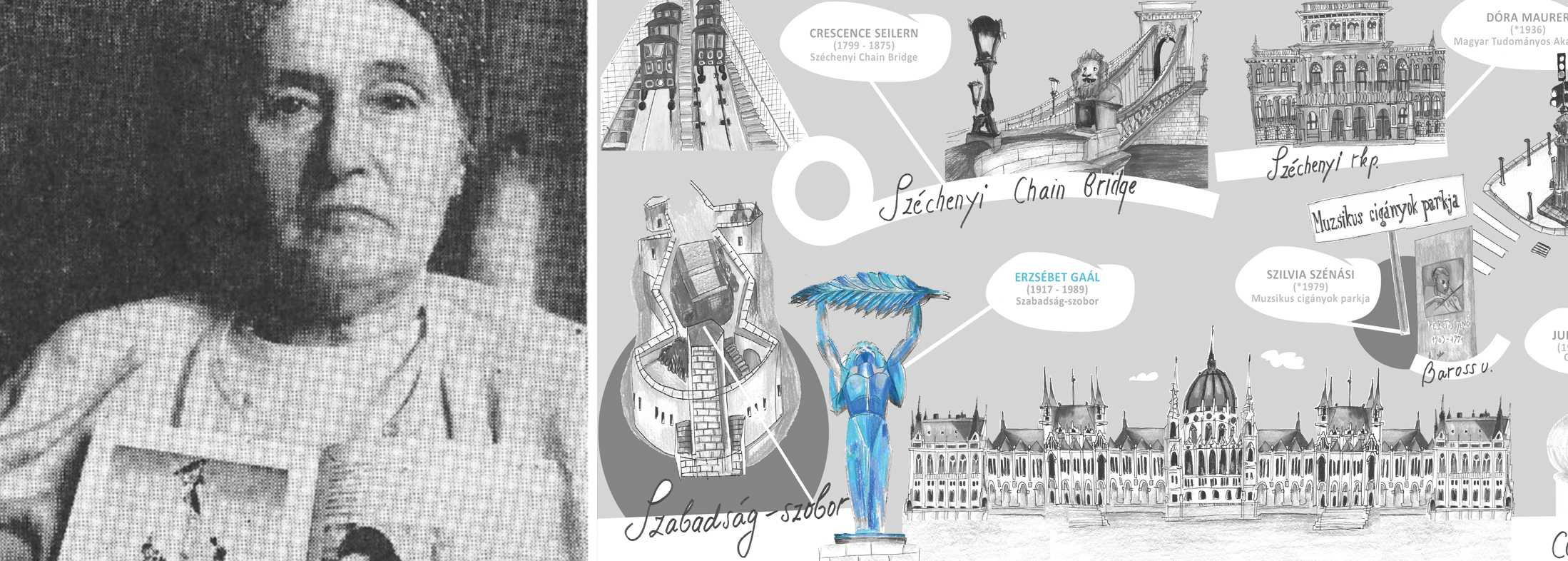

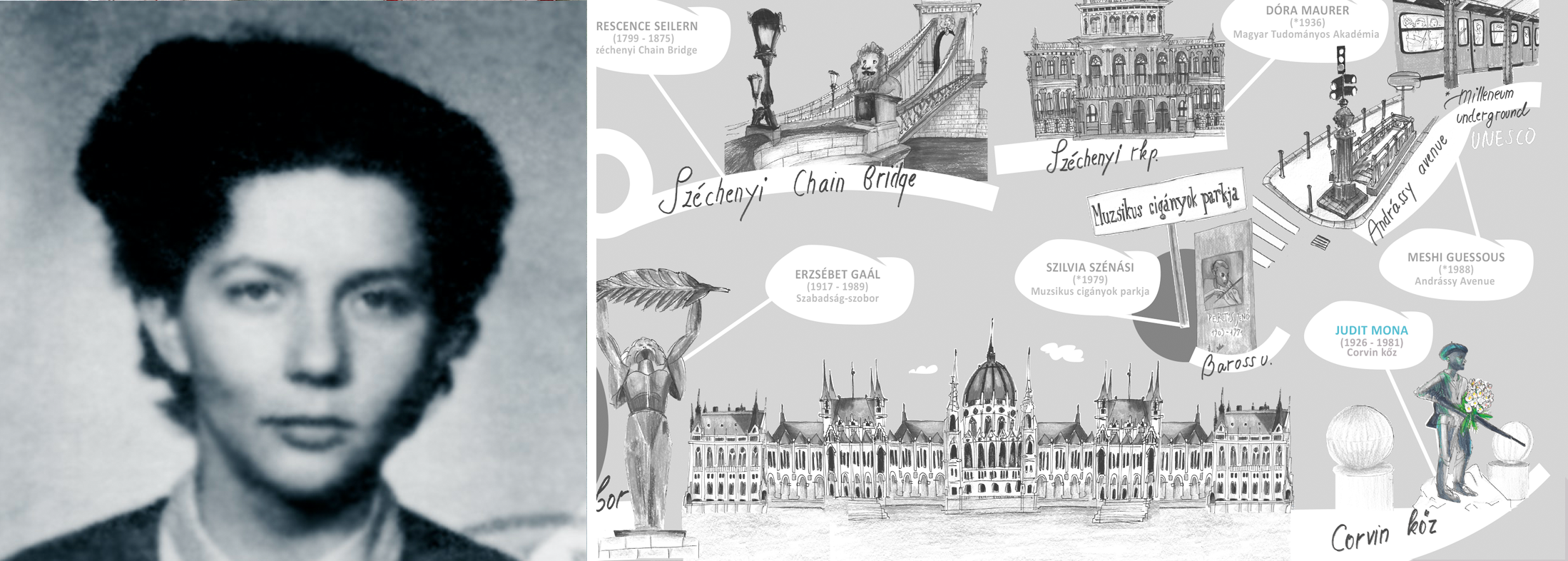

model of the Liberty Statue of Budapest (1917-1989)

Erzsébet Thuránszkyné Gaál, a 28-year-old healthcare worker, was glimpsed by sculptor Zsigmond Kisfaludi Stróbl in a tram stop in October 1945. The renowned artist had been commissioned to create a monument commemorating the liberation of Hungary, to be erected on Gellért Hill. Instead of the prima donna of the Bolshoi Ballet or other celebrities, Kisfaludi found this unknown girl from the countryside the most suitable model for the project. At first, upon being approached, the woman thought the artist was a sexual deviant and was only reassured of his intentions once he presented her with his business card.

Little is known about Erzsébet’s youth. At the time she met the Kisfaludi, she was living in a small village. The master and his model got to work the day after they met. It took three entire days for Kisfaludi to explain the position of the body, the head and the palm branch and to have Erzsébet practice the pose. She finally stood model for ten days – or, according to some, for weeks – holding up the palm branch for twenty minutes at a time. Her waist-long hair had been cut and was blown by a fan – in representation of the wind off the Danube – while she held her pose. Erzsébet undertook this task as community service for which she was offered no payment. She was not invited to the unveiling.

After modelling, Erzsébet Gaál worked as an X-ray assistant. She got married and gave birth to a baby girl, of whom she asked Kisfaludi to be the godfather. Erzsébet became something of a celebrity with the Soviets. They named school clubs and even a school after her. She was awarded the status of honorary pioneer, and many maintained correspondence with her. She met Ostapenko’s widow and Tereshkova as well. She was reunited with Golocov – a former Soviet soldier – after whom the Soviet soldier of the group statue on Gellért Hill was modelled. In Hungary, journalists and pioneers asked for Erzsébet’s photo and a few lines, usually just preceding the 4th of April, the date marking the anniversary of Hungary’s liberation. During her lifetime, she gave a number of interviews. It was in 1984 that she uttered her much quoted sentence: “You know, there have been many undeserving people that I held up a palm leaf for…”

Her private life was less of a success. Her husband left her and then died. In spite of her fame – she was simply known as “the statue” – she had financial struggles towards the end of her life; she lived in the service lodgings of the Sopron Sanatorium, in a tiny hole which they wanted to her to vacate upon retirement. In her interviews, she complained: not even the comrades would be willing to help her. Finally, she was granted a HUF 1000 pension supplement by the Presidium. After her death, in spite of her daughter’s pleas to the Party Committee, she was not given an honorary grave. Furthermore, they were only willing to cover the cost of Erzsébet’s funeral if it did not include the services of a priest. With this condition, the grieving daughter did not accept the offer. On the tomb of Erzsébet Gaál (married name: Thuránszky Tihamérné), located in Sopron, the following inscription was engraved: “Here lies the model of the Liberty Statue”.

This story is recounted by university professor and historian Andrea Pető on the bus tour “Women in the Labyrinth of Budapest”, organized by the Budapest Walkshop.

Etelka Kuntich was a sister in the Austrian-founded Order of the Daughters of Divine Love. During World War II, she lived in the Order’s convent located on Budapest’s Sváb Hill, where she also worked as a nursery school teacher. In the wake of the German occupation, the

deportations began. Sympathizers of the Arrow Cross Party, which rose to power a few months later, held spontaneous raids during which they dragged away and executed countless Hungarian Jews. During such an event, Sister Tarsitia saved Jewish children who were sheltered in the convent from being shot into the Danube, while Adolf Eichmann, a German Nazi SS-Obersturmbannführer and his men, who arrived in Hungary in March 1944 to organize deportations, were lodged at the Hotel Majestic, a Bauhaus-style building located near the convent, which still remains unmarked today.

The war brought dramatic changes in the lives of the sisters as well. During the siege of Budapest, the building was occupied by Russian soldiers. Then, following a brief, peaceful period after the war, a tractor school was moved into the convent. In 1950, after the Communist regime change, all monastic orders were disbanded and the State seized control of all church property. The sisters were forced to seek employment as civilians, which resulted in a difficult situation since they were stigmatized because of their monastic background. They were rarely able to find employment within their original professions, as nurses, or school and nursery school teachers, and even if they did, their past at the convent had to be kept secret.

Etelka Kuntich ended up working as a loader in a mine, where, due to the hard physical labour she had to perform, her health deteriorated. Later, she was entrusted with the task of organizing a local nursery school in the nearby village of Olaszfalu. The former nun devoted her entire life

to educating children. The children whom she had saved during the war remained in contact with her even as adults, up until her death in 2009. They were instrumental in her receiving the Yad Vashem Institute’s honorary title of Righteous among the Nations in 1998. The community of the village of Olaszfalu, albeit unaware of her activities during the war, erected a memorial to Etelka Kuntich – not lifesaving nun, but legendary nursery school teacher.

Judit Mona was born into a family with three children in Tápiósüly. Her parents had a leftist affinity; her mother joined the Social Democratic Party, her father guarded the borders of the Hungarian Socialist Republic as a soldier of the Red Army. She studied medicine, and in 1951, she married her fellow student, Attila Lehoczky. Their son was born in 1955.

On 23 October 1956, on her way home from work, traffic came to a standstill: the Stalin statue was in the process of being taken down. She also witnessed the seizure of the radio station. At the beginning, she provided medical help in Kőbánya, and after a few days, she joined the fighters at the Corvin Passage. She became the chief physician in Práter Street and obsessively worked in a makeshift operating room. She also treated members of the State Protection Authority (ÁVH). When a rebel expressed his disapproval, suggesting harsher treatment, she replied: “Fighter, how can you speak like this? That would make us just like them.”

On 6 November, along with the majority of Corvinists, she set off toward the western border. The couple had no choice but to leave Hungary together in late November, without their child. First they lived in Vienna, then in Geneva, while also maintaining contact with the Hungarian Revolutionary Council. In a bold move, her husband managed to bring their child out of Hungary.

Shortly after, they moved to the United States, first to New York, then to Buffalo, where they changed their family name to Lehotay. They encountered difficulties when the Americans refused to accept their Hungarian diploma, so they had to start their professional careers over. Judit began

to work as a pathologist in various hospitals, then obtained her medical degree in New York. A successful career followed: she became a forensic expert, gained membership to numerous American scientific associations and became the first female member of the leadership of the National Association of Medical Examiners. Her achievements attracted a significant amount of publicity.

Judit found it important to hold on to her Hungarian roots. She became a leading member of the US Federation of Hungarian Freedom Fighters. She was also involved with organizational activities of the American-Hungarian scouting movement. She died at a young age, in 1981.

13 May 1799 – 30 July 1875 (lived 76 years)

Countess, wife of István Széchenyi

Countess Crescence Seilern-Anspang, was born in Brno of Moravia, to a well-connected family, albeit of moderate fame. Of her numerous suitors, it was Károly Zichy Jr. whose marriage proposal the beautiful young woman accepted in August 1819. She was twenty years younger than her new husband, with the added responsibility of also taking care of his seven children from his previous marriage. As an honourable wife and mother, she dutifully took on these responsibility.

In 1823, the mysterious workings of fate sent the young and ardent Count István Széchenyi to cross paths with Crescence. Their personalities could not have been different: the Count had an impulsive nature with a serious – at times even morose – disposition, while the Countess was full of life, possessing a light-hearted, cheerful demeanour. Széchenyi pursued Crescence relentlessly, but, in spite of his frequent amorous overtures, she sent all his letters back unopened. There was even an occasion at the theatre in Bratislava when she simply walked out on him. She was secretly enamoured of the young man, but she wanted to protect her virtue at all costs.

The Count then decided to win Crescence’s admiration on the merit of his accomplishments; he sublimated his amorous anguish by throwing himself into his work. In 1832, he set off to England to organize the construction of the first permanent bridge on the Danube (which we know as the Széchenyi Chain Bridge today). The bridge – which was thus born of the inextinguishable flame of the Count’s desire for Crescence – later became the chief accomplishment of his lifetime. The bridge was finally handed over in 1849. Today, city dwellers are using Chain Bridge more or less in its original form. Before starting his work on the bridge, Széchenyi had worked on opening the Lower Danube up as a trade route (1830). It was in connection to this endeavour that he was once again travelling on the Danube when he heard of Count Zichy’s death. After the year of mourning was over, they got married on 4 February 1836 in a church on Krisztina Square, in the presence of only six witnesses.

They spent their days partly in their residence in Pest overlooking the Danube (and the immense Chain Bridge, inspired by Crescence), and partly in the Castle in Cenk/Tâmpa. In addition to his seven children, the Count looked after his wife’s seven adopted children as if they were his own. In the following years, Crescence gave life to two more sons. She supported her husband in everything – to please him, she even learned Hungarian.

1848 brought a grave turn. The count had a nervous collapse; he envisioned the country’s final fall and felt terrified that he would bring death to his family. Consequently, he asked Crescence to divorce him. She remained strong, however; she refuse to leave her husband’s side and found him accommodation at the sanatorium in Döbling, where he would receive the appropriate care.

After her husband was moved to Döbling, Crescence relocated to Vienna in order to be near him as often as possible. They kept in constant contact; they were especially preoccupied by the future of the family. After Széchenyi’s suicide in 1860, his loyal wife remained in mourning until her own death in 1875.